Stuart Brodsky has dedicated his 25-year career at Cannon Design in Chicago to designing and planning educational facilities. At a firm renowned for its K-12 expertise, Brodsky’s projects have received national recognition by organizations such as the American Institute of Architects, the Council for Educational Facility Planners and the American Association of School Administrators. He served on the task force for the development of the Illinois Resource Guide for Healthy High Performing Schools with the Healthy School Campaign. He currently co-chairs the Illinois Chapter USGBC Green School Advocates Committee and serves on the advisory board of the Green School National Network. Brodsky has taught extension courses on green schools and frequently lectures to community and professional organizations on sustainability issues.

Stuart Brodsky has dedicated his 25-year career at Cannon Design in Chicago to designing and planning educational facilities. At a firm renowned for its K-12 expertise, Brodsky’s projects have received national recognition by organizations such as the American Institute of Architects, the Council for Educational Facility Planners and the American Association of School Administrators. He served on the task force for the development of the Illinois Resource Guide for Healthy High Performing Schools with the Healthy School Campaign. He currently co-chairs the Illinois Chapter USGBC Green School Advocates Committee and serves on the advisory board of the Green School National Network. Brodsky has taught extension courses on green schools and frequently lectures to community and professional organizations on sustainability issues.

Q: What LEED projects have you recently completed and what was unique about these designs?

Q: What LEED projects have you recently completed and what was unique about these designs?

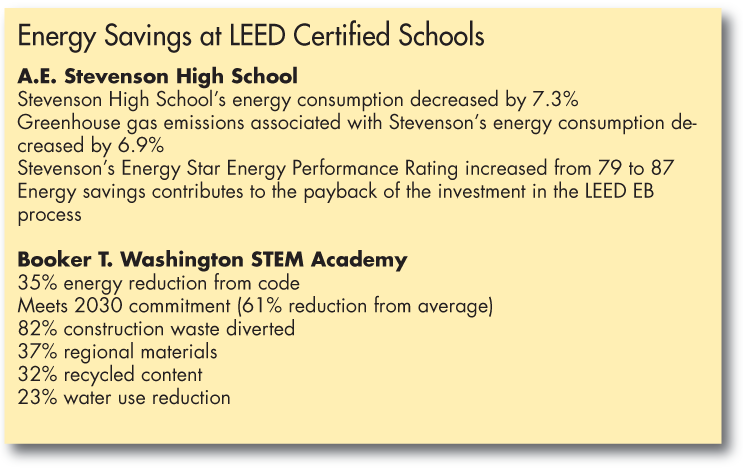

A: We recently received LEED Gold certification at the Booker T. Washington STEM Academy in Champaign, Ill., and finished the first LEED-EB (LEED certification for Existing Buildings) Gold High School at A.E. Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Ill. For the A.E. Stevenson LEED-EB project, it was more about creating and maintaining energy efficiency throughout the school. School officials worked closely with the design team to see themselves at the end of the certification period and into the future. They also had a goal of finding opportunities to integrate the LEED certification project with the curriculum, so the vision and goal-setting process allowed them to do that. In order to receive LEED-EB certification, certain prerequisites and standards needed to be met, including energy efficiency best management practices, outdoor introduction and exhaust systems and some sort of green cleaning policy, among a list of about nine prerequisites.

Booker T. Washington received LEED Gold certification in April. It’s a magnet school, focusing on STEM — science, technology, engineering and mathematics. The project has high levels of performance not only on an education side but also on an energy side, and that was important to the school district. They wanted to implement energy performance measures in many existing schools with lighting retrofits and wanted to install geothermal HVAC units in existing schools. Energy targets were established with the project. That was an important initial phase of the process, to establish a high-performance direction for the project, because it not only was the best thing for the future, but it allowed them to access grant-funding opportunities that exist in Illinois.

Setting goals for LEED certification allowed them to access grants, including one from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. The other goal they had set early on in the process, even before we were selected, was that they wanted the new schools in the district to be LEED-certified. They share the same goal as A.E. Stevenson, of wanting to utilize the building to unite the community and involve the community in a transparent process.

Q: What is the 2030 commitment and how do schools meet this standard?

A: There’s an organization called Architecture 2030 that created something called the 2030 Challenge. It was a challenge that was put out there to help anybody designing or building a building to have a benchmark for how energy-efficient that building needs to be now, and with an end goal of having buildings that are eventually carbon neutral. Given where we are with technology today and the cost of the systems that exist right now, it’s difficult for most clients to achieve that. So what Architecture 2030 did was create a step program where there’s a new threshold that’s set every five years between now and 2030. For buildings that are built between 2010 and 2015, the goal is to have a 60 percent reduction from an average building. Booker T. Washington meets that reduction, and incidentally, this is a goal that wasn’t necessarily set by the client. There’s also something called the 2030 commitment — a program started by the American Institute of Architects that firms sign on to as a commitment to measure the performance of the buildings they design. Cannon Design is a signatory of that program.

Q: Have you ever worked on a LEED-EB project before your recent project at A.E. Stevenson? What challenges were you faced with?

A: This isn’t the firm’s (Cannon Design) first LEED-EB facility, but it is the first one that I have personally worked on and it’s the first school that we have done that way in our office.

The challenges of LEED-EB are not so much in the design process as it is in the targeting and goal setting. It’s not a new building so you don’t have as much control over the process, and it’s a process of working with the client and having to develop a series of policies and procedures and essentially changing their culture to become greener and more sustainable. These definitely are not negative challenges. They’re all good challenges, and the goal becomes, “How do you operate to become more sustainable in lieu of what we’re accustomed to?” — which is typically to design something to meet a standard. LEED-EB is a unique system where we have to work with our clients to help them operate differently.

Q: How has the concept of sustainable building evolved over your 25-year career?

A: I think early on when we first started designing LEED-certified designs — back in 2001 to 2003, when LEED first started kicking in — the goals were usually more modest to become only LEED-certified. What LEED has done, though, is really transform the marketplace so that the industry is all rallied around sustainability and measuring where you are.

When LEED projects first started, none of that really existed to the degree it does now. Now you can find LEED-certified materials easier and there have been improvements in system design in the last decade with available technology at lower cost. We’ve seen LEED adopted by more clients and recognized as being something that can help improve the quality of the building without necessarily adding a significant cost, whereas early on there was a perception that it only added cost and you might not get any payback or benefits from being LEED-certified. LEED has also branched out and LEED-EB was not really being implemented on school projects back then, it’s really been more recent. There’s a big push now to green all the existing buildings in the country. The Green Building Council estimates that there are 133,000 schools in the U.S. and they have a vision of seeing every student in a green school in this generation, so there are a lot of schools we need to green every year. The adoption of LEED-EB has become more of a focus more recently in schools than it has in the past. The focus used to be “You can’t really do anything unless you’re building a new building.” Now that philosophy has really changed.

Q: How much do schools save by implementing green building materials or schools that are LEED certified?

A: Typically, a LEED school is going to be 25 to 50 percent better in energy use than a co-compliant school. States have certain standards, and for Illinois, Booker T. Washington School is 35 percent better than that standard. That’s a comparison for when you build a new building, but for existing buildings the tool that they’re measured against right now is called a Consumer Builder Index. The Green Building Council has estimated that the average green building has a 35 percent reduction in carbon emissions. A LEED building shouldn’t have to cost you more money just to design it to meet LEED standards. However, there are some systems that will cost facilities more upfront — like a geothermal system, for example.

Q: What are some options for schools that don’t necessarily have the funds for high cost energy efficient upgrades?

A: There are a lot of sources out there that give many different ideas and usually those are referred to as the 10 low-cost or no-cost improvements. They can be really simple things like managing their energy use and scheduling it and seeing where energy is used in the building — it’s a simple operational change that can be made and doesn’t necessarily cost more money, it just requires a thought process and plan of how to do it. Also, having regular maintenance on your mechanical system will help it operate more efficiently. Educating students and teachers also helps to benefit the energy efficiency of a school by simple things like turning the lights off. There are programs out there that have proven that if a school went through an educational program they can actually change behavior within the building and allow students and teachers to take responsibility for energy use in the building.

Q: What is the future of LEED buildings?

A: LEED is constantly improving the standards and the way they measure performance. There’s a strong interest in looking beyond the building itself. Two examples of that include looking at the life cycle and how efficient the building is over time, and there’s also an interest in looking at the effect of the source of the energy fuel that’s being used. There’s also a real strong interest in studying and ramping up the understanding of toxicity of materials and developing new materials and better standards for what compounds are going into our materials and how they affect health in our building. I think that over time, we’ll measure and understand the materials we have and also set goals.